Architecture and Tools Decision: Rails + React = BFF

When we began to modernize our company’s main software, we need to choose an architecture that could be as stable as it was for the last 20 years and at the same time, allow us to use one of the best alternatives to build a highly interactive and complex front-end.

So, to embrace the innovation while keeping a solid foundation, we decided to work with our main web framework Rails, with the React front-end, an amazing feature of one of Rails more recent versions.

The Ruby (and Rails) are our main programming language + framework for about 6 years to modernize our almost 20 years old legacy system. We already have a lot of interesting tools working together, like MongoDB, Redis, RabbitMQ, PostgreSQL, etc. All of them with fantastic libraries/support for Ruby.

Besides that, our front-end team is growing fast and wants to apply what they’ve been learning (in theory and practice) every day with React.

Mixing everything!

With all of this in mind, our decision was not so difficult, because Rails recently brings pretty decent support to use some of the modern Javascript frameworks (react, angular, vuejs) as a front to a web-app.

But we don’t want it to become a new monster after some months when we passed the main features of our app to this new project, so we think: How we could use these new features? Which is the architecture that mostly adapts to our needs?

We thought about GraphQL, but we don’t want to rewrite all our main API’s at the beginning of the process of rewriting our already big legacy system (Maybe GraphQL could be another “decision post” in the future…)

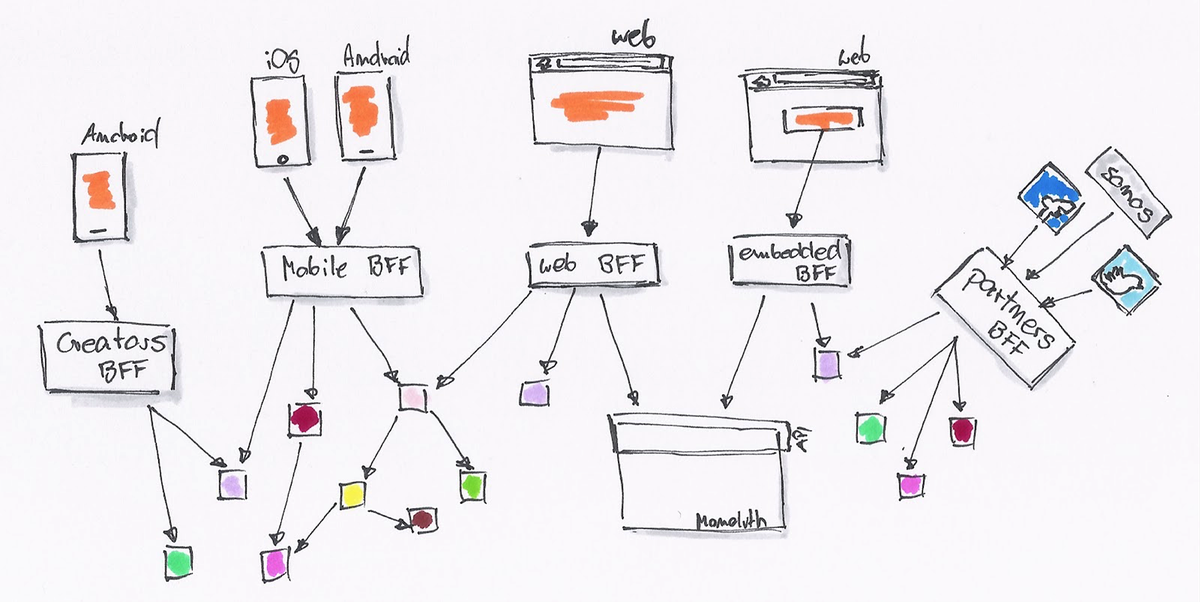

After some research, we listen about a pattern that is emerging, mainly in the microservices world, that is called “Backend For Frontends” (or BFF for short).

Final decision: BFF to the rescue!

This option shows up in one of the ThoughtWorks’ technology radar, and you could read deeper articles here and here. The BFF is an attempt to bring backend support for each kind of client that is consuming our services. Its main goal is to decouple the APIs/microservices from their consumers.

Basically, what we do is include one more layer (the BFF) between our APIs and a frontend client, attending its individual needs. For example, let’s say that our mobile app is simpler than our web-app, and in the list of customer’s items don’t show all the details about each one of them.

These backends should (ideally) be developed by teams aligned with each frontend to ensure that each backend properly meets the needs of its client.

If we request the information for the same API route for both, the mobile app will receive all the data, as the web-app, but will discard most of it, consuming mobile bandwidth with useless information. To solve this problem, we can develop two BFF’s, reading the same API route, one returning everything and another returning only a subset of the information that will be used by the mobile client.

Final Thoughts

Sure that it’s a contrived example, but when you need to call three, four, five or even more routes to render one page and all its options, each call that brings only the strict necessary will save you and your customers bandwidth, less work to frontend to join all that info, since the BFF already did it.

Besides that, maybe you can apply some rules authorization/authentication/business rules, giving to frontend just the information about possible errors, unauthorized requests or links to more features accessed by that page/customer.

As the possibilities are so numerous, I strongly recommend that you read both of the articles cited above, to understand even more of this pattern and judge if it adapts to the needs of your company.

Did you already used this architectural pattern in some of your companies app? What are the challenges that you faced? What’s the best/worst part of this pattern?

Let me know if you liked this post! If you have any suggestions or critics, post a comment below!